By Lisa Robinson

The Impact Interview Series is a collaboration between WITNESS and BRITDOC, who produce and host the Impact Awards for independent documentaries. Read more about the Award and this year’s five winning films here.

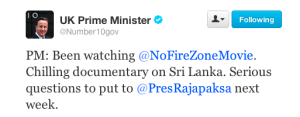

It’s not every day that the Prime Minister of the UK watches your film and is compelled to Tweet about it – publicly calling out the president of another nation and adding allegations of war crimes to his diplomacy agenda. But that’s exactly what happened to Callum Macrae after his investigative documentary, No Fire Zone: The Killing Fields of Sri Lanka, first made headlines last fall.

No Fire Zone is a chronological account of the final months of Sri Lanka’s 26-year civil war, where an estimated 40-70,000 civilians died after being systemically shelled and left without adequate food or medical supplies in so called “No Fire Zones” imposed by the Sri Lankan government. Recently awarded an Impact Award by BRITDOC (and nominated for an International Emmy), the film’s core goal was to advocate for the UN Human Rights Council (OHCHR) to vote for an independent, international inquiry into these and other ongoing human rights abuses in Sri Lanka.

Less than a year after the film’s initial release, those goals have already been met. In March 2014, OHCHR passed a resolution calling for an in-depth investigation. This, among many other campaign milestones, led Callum and his team to revise and release an updated, extended cut of the film just last month.

The film stands out to WITNESS because of its use of citizen shot video on mobile phones by both civilian victims and perpetrators of the abuse – as well as the evidentiary role that this footage played in proving allegations against the Sri Lankan government. Last fall, WITNESS featured the film on our blog; today, we’re back with an update from director Callum Macrae.

Lisa Robinson: What was your process in choosing to tell this story about Sri Lanka’s civil war?

Callum Macrae: The process began when I was asked to direct a TV documentary for Channel 4 in the UK about the events at the end of the war. This itself built on reports by Channel 4 News during the war. But the more I looked into it and the more new evidence emerged, it became clear that we needed to do more than this one TV doc. I’ve covered a few wars in my time, but this story was so extraordinary – the scale of the massacre so awful and the Sri Lankan government’s success in keeping it, to all intents and purposes secret, was so disturbing that telling the story as widely as possible became almost a duty.

But there were a few factors that were critical in our decision to go on and make the feature-length documentary, No Fire Zone. The first was the reaction of the Sri Lankan government to our journalism – a combination of denial and wild accusations that we were somehow apologists for the Tamil Tigers (who we had in fact accused of committing war crimes, using terror tactics, child soldiers, and suicide bombing attacks on civilians). When someone attacks the veracity of your journalism it does make you determined to defend it.

But more important was that with every day that passed, more compelling evidence was emerging. This evidence demonstrated the sheer scale of the crimes committed by government forces in the final weeks and days of this terrible conflict. At the same time more crimes were being committed every day against the Tamils of the north and east. It was clear this was not an exercise in historical accountability – there was an urgent need for the truth-telling, which is an essential prerequisite for any kind of progress to political solutions, peace and reconciliation.

It was also clear that the Sri Lankan government was neither willing nor capable of initiating such an enquiry itself.

In a sense, we wanted to make a film – designed to be taken to audiences around the world – which would act as both a definitive film of record and a call to international action.

Your film includes significant video evidence by both victims and perpetrators. How were you able to obtain this footage?

There are effectively two main tranches of video evidence in the film. The first set comes from the Tamil side. Essentially it is a video record of the day-to-day horror of life in the No Fire Zones. It was filmed by a variety of people including civilians and doctors – although most of the footage came from people who had worked for the Tamil Tiger “media” office. Originally they expected to film propaganda for the Tigers, but instead found themselves filming the misery of civilians as government forces shelled them mercilessly. Though it should not be forgotten that this was a misery in which the Tiger leadership was partially complicit in that they refused to let the civilians leave. This video footage was sent out by satellite phone links to the Internet, and was filmed by people who – whatever their previous role – displayed astonishing bravery day in, day out.

The second set of videos comes from the perpetrators themselves and includes terrible images of executions, torture and the aftermath of sexual assaults. These videos were circulated among Sri Lankan army soldiers. Some of this footage was no doubt sold – although we never paid for any footage and have always made clear that we never would. But I am also confident that some of this footage emerged because it ended on the phone of some perfectly honourable Sinhalese soldier who said: “This is not what I was fighting a war for.”

Much of the rest of the footage came from sources we cannot identify, but some opposition websites played a crucial role in collecting this material. War Without Witness collected huge amounts of material shot within the No Fire Zones. A key source of the “trophy” footage shot by Sri Lankan armed forces is Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka, an organisation of extremely brave Sri Lankan journalists from all communities, many of whom were forced into exile because of threats to their lives.

As a follow-up to my last question, based on your experience in verifying mobile shot footage, do you have any advice for activists who are documenting abuse for future evidentiary purposes?

If you are actually filming this kind of footage, there are a number of things that are important or can be very helpful to those you hope will use it for evidential purposes. It goes without saying that your first duty is to ensure your own safety and the safety of those you are filming – both immediate physical safety and also longer-term security in terms of dangers if you – or individuals on film – are identified. I’m sure activists are very aware of that.

Once you have taken such security measures as best you can, then if safe to do so, it is always good to supply as much additional evidence as possible. This will seem obvious, but if you are using a camera with GPS, make sure it is enabled. If it has a date and time, make sure they are set correctly. (You don’t need to set the date and time to be burnt in to the image. It should be recorded perfectly adequate in the metadata.) Don’t just film the events, state on camera as soon as possible where and when you filmed it. If you have time and it is safe to do so, keep the camera running and film a wide-shot, or overview of the scene to show the location. If you have a map or street plan, film that and point to where the events took place. If you have a newspaper film the front page and date, which will at least demonstrate that the footage was taken after a certain date.

As a filmmaker, or if you are compiling such evidence shot by others, then there are other things you can do to verify the footage, but these are not cheap. For example, for No Fire Zone, we had the key video and still images showing the executions and aftermath of sexual violence analysed by two sets of experts. First, we had forensic image and video analysts (who work for British Courts) analyse the footage – looking for any evidence of manipulation, editing or any technical inconsistencies. In most cases they were also able to identify the device on which it was filmed and check that this device was consistent with what would be available to the people doing the filming.

Secondly, we had the footage and stills analysed by a leading forensic pathologist – who also acts as an expert witness in UK courts – and he was able to analyse the nature of the injuries, the type of damage, the way bodies behaved, blood spatter etc., to ensure that these events could not have been faked.

Finally, because the soldiers’ language makes heavy use of slang – but is potentially significant evidentially – we had their conversations translated two or three times by different translators and then had those different versions mediated by one more translator.

How were you thinking about the campaign and its impact during planning and pre-production? Did your thinking about impact evolve during the project? And if so, how?

Yes, and our ambition was actually very high. Astonishingly few people really knew of the scope of the massacres in the final weeks of the war. We wanted to bring these events to the attention of the world. We also wanted to do what we could to persuade the international community to launch an international inquiry into the events.

That put a particular responsibility on us. We were gathering information and evidence, which we hope will be part of a formal judicial process one day. It meant we had to treat that evidence with particularly careful respect.

We also knew that the film would be energetically attacked by the government of Sri Lanka and its supporters. And that added further fuel to our determination to ensure that there could be absolutely no question-marks over the authenticity of our evidence.

But we knew this also had to work as a powerful narrative – it had to engage. We hoped the film would persuade and convince everyone who watched it. Both politicians, diplomats and the people to whom they must (or should!) answer – the public. It seems that it did work on all these levels. It is not often that you see diplomats and politicians in tears as we have experienced at screenings.

What we had not perhaps predicted was the way that over the past year the evidence has continued to emerge. As fast as the Sri Lankan government issued denials of our contentions, new evidence emerged and has proved we were right. For example, the Sri Lankan government denied the Tiger TV presenter, Isaipriya had been executed as we claimed, insisting she had died in combat. Then we obtained footage showing Isaipriya being captured, alive. We then obtained further photographs showing her in captivity, uninjured, with hands tied behind her back, and accompanied by identifiable government soldiers.

As each new bit of evidence emerged we were able to release it and generate more interest in the film.

If there is one person that you hope sits down to watch this film, who would that be? And why?

Actually, many people who I wanted to watch this film already have. I hoped British PM David Cameron would watch it before he went to Sri Lanka to attend the Commonwealth Heads of government meeting last year. He not only watched it, but tweeted:

He then went on to consistently raise questions of human rights, and endorsed the call for an international enquiry into the war crimes when he was there. I wanted national missions to the UN Human Rights Council to watch it – and many did, before going on to vote for the establishment of an international inquiry.

However, there are many who I still hope will watch it. National representatives of independent and non-aligned countries who may mistakenly be giving credence to the Sri Lankan governments phoney attempts to portray the call for justice in Sri Lanka as some kind of “western” bullying of a small independent nation. We know that where representatives of such non-aligned countries have seen the film, they have quickly understood how bogus that claim is. That this is about universal human rights. The Sri Lankan government was anxious to portray its attacks on the Tamils as part of the west’s “War on Terror” when it suited them. Their subsequent attempt to hide their crimes under a phoney cloak of “anti-imperialism” is a fraud. Getting this film to Latin America, to Africa and non-aligned states is important.

Finally, we want this film to be seen as widely as possible by people of goodwill from all the communities of Sri Lanka. To aid in that process we are currently having the film translated into Sinhala.

Tell us about the impact the film has had since its release. Is there one example you are particularly proud of?

The film really has had more of an impact than we could have hoped for.

International media coverage was remarkable, including hundreds of articles, TV stories and interviews. Some were film reviews, but mostly news that was generated by our revelations. In addition, there were OpEds and editorials in the UK Guardian and the Times of India, among others.

It has been discussed in parliaments around the world, generated mass demonstrations in support (in India) and against (in Sri Lanka).

The most dramatic result – and a number of senior Human Rights activists have generously said that we played an important part in this – has been the establishment of an international inquiry by the UN Human Rights Council and the transformation of the Commonwealth summit into an international examination of the allegations.

What have been viewers reactions to your film? Were there any surprises?

There is no doubt that the film does have an enormous impact on people who see it. Often local history has given added resonance. For example, in Buenos Aires, I spoke at a screening hosted by the Canadian Embassy and it was attended by leaders of the campaign for the disappeared in Argentina’s dirty war – as well as by the Argentinian Human Rights Minister. The scale of the disappearances in Sri Lanka had real resonance for them. Then earlier this year, I spoke at an emotionally charged screening in Kiev, Ukraine, where the film resonated powerfully because of that nation’s historical experience of mass killings.

The film has also been widely welcomed by the Tamil diaspora. Activists have suggested it has strengthened the resolve of Tamils to fight for justice in the belief that the world is now beginning to listen. Perhaps more surprising has been its endorsement by people who were there – the traumatised civilian survivors. I had been very worried that survivors would find watching the film deeply traumatising. In fact I have been told that many have found it helpful – it had a cathartic effect in that they felt it helped other people understand what they had been through.

For campaign updates, connect with Callum Macrae on Twitter and visit the film’s website.

Lisa Robinson is the External Relations Coordinator at WITNESS.